period of 4 s ⇒ 2 ms

Note that height of pulse is very irregular

Tuan Do, UCLA Astronomy Graduate Student

Neutrons will become relativistic if density becomes too high. Upper limit for neutron stars is about 3.5M₀: beyond that we get black holes. Upper limit is not so rigorous: can ignore electron interactions but not neutron interactions

predicted by Oppenheimer (yes, that one) in 1935.

| Very regular radio pulses, period of 4 s ⇒ 2 ms Note that height of pulse is very irregular |

|

| All lie close to Milky Way (i.e. in plane of galaxy).

Therefore must be related to stars |

|

|

Best known is Crab. Known to be remnant from supernova in 1054 (seen by Chinese) Pulsar at centre has period of ∼ .03 s |

|

| Optical pulsing observed by TV or strobe |  |

| Pulses at all wavelengths, in synch. |  |

| e.g Vela |

and the Crab |

| And we can listen to them! |

What pulses? |

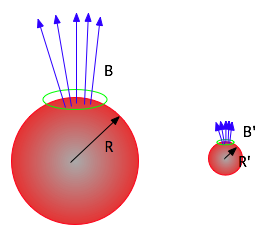

Solar B ∼100 G ∼ .01T, estimate core fields ∼ 106T: What can we expect Neutron star fields to be?

| Magnetic flux must be conserved

\color{red}{

\begin{array}{l}

\varphi = \int {\vec B.d\vec A \approx \pi a^2 B} = \pi a^2 B'\left( {\frac{R}{{R'}}} \right)^2 \\

\Rightarrow B' = B\left( {\frac{{R'}}{R}} \right)^2 \\

\end{array}}

|

|

| Charged particles travel along lines of force, hence can only escape from poles of neutron star. Hence "lighthouse"mechanism: we only see pulsar when mag. pole points towards us |

Do we see all the pulsars?

No, because they would have to be oriented so that they point towards us. rotation period will slow down...

Hence probably large number of radio-quiet neutron stars: essentially impossible to see.

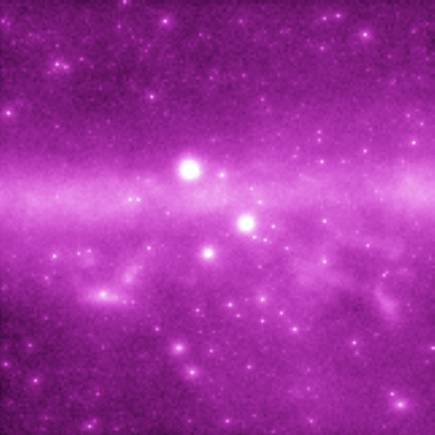

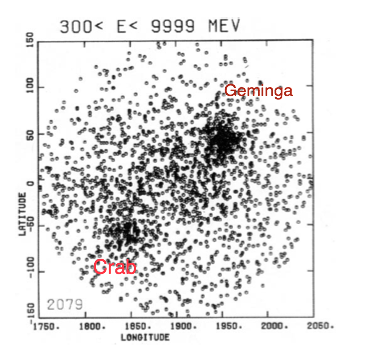

| Since neutron stars are so hot we see them in X-rays and γ-rays. This shows how a new satellite (GLAST) will see the sky: the brightest object is he Crab and the second brightest....... Geminga: a pulsar that had only been seen in γ-rays until it was identified as a very faint star |

GLAST Gamma Ray Sky Simulation Credit: S. Digel (USRA/ LHEA/ GSFC), NASA |

| Orignally seen in first (circa 1973) by SAS-2 γ-ray astronomy mission: enhancement of !~100 photons! |  |

| Spectrum is weird!

Note:

|

|

| Name | Crab | Vela | Geminga |

| Spec | PSRJ 0534+2200 | PSRJ 0835-4510 | γ195 + 5 |

| P0 (s) | 0.03308471603(11) | 0.089328385024(4) | 0.237102411 (.2370974531) |

| P1 (s/s) | 4.22765(4) ×10 − 13 | 1.25008(16) ×10 − 13 | 1.0976$ \times 10^{ - 14} $ 1.0976 ×10 − 14 |

| f0 (Hz) | 30.2254370(1) | 11.1946499395(5) | 4.21758680093 (4.217675) |

| f1 (s−2) | -3.86228(3) ×10 − 10 | -1.5666(2) ×10 − 11 | - 1.95211$ \times 10^{ - 13} $ (-1.95249675 ×10 − 13 ) |

| f2 (s−3) | 1.2426(5) ×10 − 20 | 1.028(1) ×10 − 21 | |

| f3 (s−4) | -0.64(5) ×10 − 30 | ||

| Epoch | 40000.00 | 51559.319 | 53630 (48400) |

| Distance (kPc) | 2.00 | 0.29 | .157 |

| Age | 1.24 ×103 | 1.13 ×10 4 | |

| Power: W | 1.2 ×1038 | 8.5 ×1037 |

SS-433 found as star with very unusual spectrum |

|

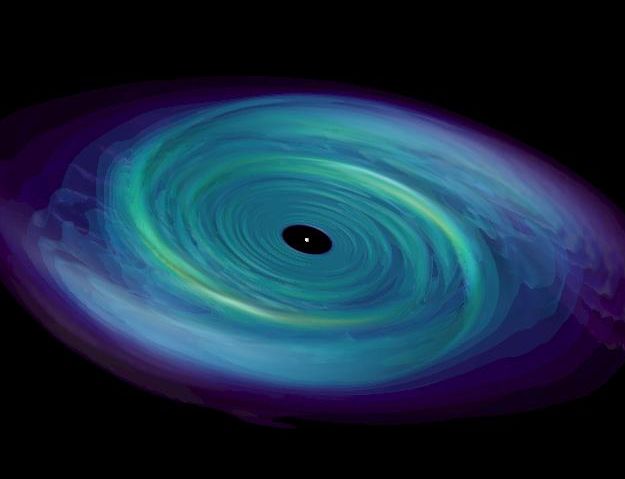

| This is something new! Narrow jets travelling at 1/5 speed of light are shot out of poles, probably formed by thick accretion disk around neutron star or black hole: "cosmic lawn sprinkler" |  |

presented his ideas to the Royal Society in London in 1783. and astronomer Pierre Laplace, in 1795.

Why do all masses fall at same rate? All normal forces (e.g. electrical, friction, elastic...) don't produce same accn in all bodies.

The first m (inertial mass mI) measures how hard things are to accelerate (2nd. law), the second (gravitational mass mG) measures gravitational force

Maybe gravity is somehow a fictitious force (?!?!?!?)

so a = g only if the "inertial mass" is the gravitational mass. Can demonstrate this is true to 1 part in 1012 (Eötvos experiment).

| Suppose you are in a stationary elevator, and a bullet is shot horizontally, it will fall due to gravity.. |

| Suppose you are in an accelerating elevator, and a bullet is shot horizontally, it will appear to fall.. |

| Unless you look at it in the earth frame |

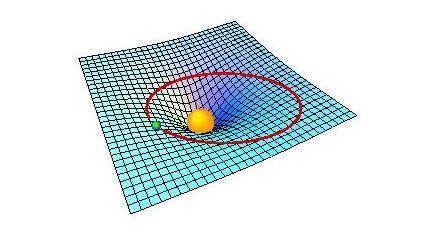

| 2. There is no such thing as gravity, it's just that masses distort space-time in their neighbourhood |

|

"Lenses extend unwish through curving wherewhon till unwish returns on its unself" e.e.cummings

Statutory Warning:This is a fudge: you cannot treat light as a massive particle, nor can you handle a very strong gravitational field as if it were a weak one......

(there are actually two factors of 2 error which cancel out.....weren't we lucky!)| A ball thrown up near the earth's surface will lose energy. |  |

|

|

| What does this look like? As long as speeds are small, exactly the same as Newton (Ha!), but if velocities are "large" then the force gets changed

Fact that orbits are closed is "coincidence" not true for any potentials except r2, 1/r and 1/r2 Hence get "rosette" orbits. |

|

Much less dramatic in practice: perihelion (closest approach to sun) of Mercury advances by 43" arc/century

| And light gets does bent: this is a very large cluster of galaxies, which acts as a very large (and rather bad!) lens. It produces several images of a much more distant galaxy |  |

| A black hole is the end product of star with > 10 M₀ how do we see it, since black holes are black: as the bumper sticker says. |  |

| If we are really lucky....(or unlucky) as a gap in the sky |

Too Close to a Black Hole Credit & Copyright: Robert Nemiroff (MTU) |

| But more likely via the "accretion disk" which will have velocity ∼ c at inner edge, so temp well into X-rays |  |

So want binary, with invisible heavy companion with M > 3M₀, emitting X-rays

Prime candidate is Cygnus X-1, which agrees with position of a massive blue star HD 226868

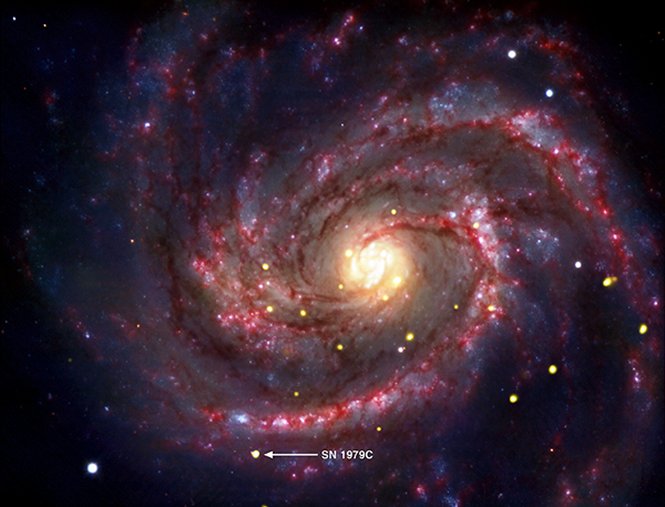

| Best case for a recent black hole: precursor probably 20Mo |  ESO/Chandra picture |

| Hard X-ray spectrum, hasn't changed over 20 years, consistent with accretion disk feeding central black hole. Note primary source seems to be BH at centre of galaxy |

|

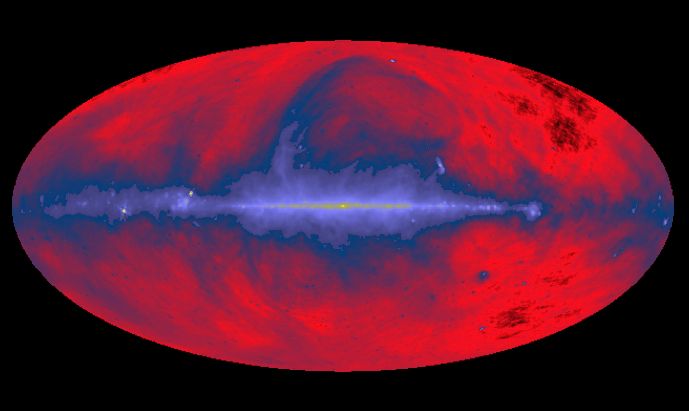

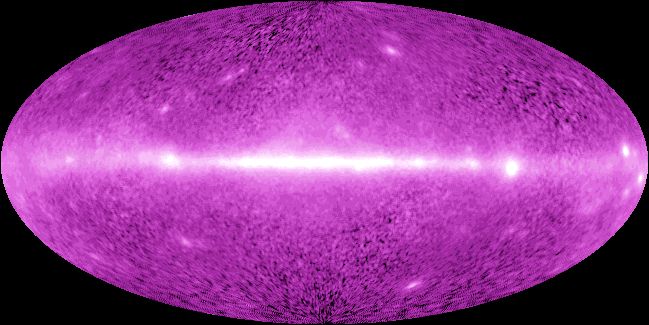

| Note there is a LOT of evidence for supermassive BH at the centre of galaxies: Milky way in radio: note very intense source at centre |

Credit: C. Haslam et al., MPIfR, SkyView |

| and γ-rays from the EGRET satellite |  Credit: EGRET Team, Compton Observatory, NASA |

| Galactic Centre Not visible directly (too much dust)as the bumper sticker says. |  Credit: W. Keel (U. Alabama, Tuscaloosa), Cerro Tololo, Chile |

but strong radio source

| We can see through the dust (partially) with infra-red: note how dense the star field is |

Credit: 2MASS Project, UMass, IPAC/Caltech, NSF, NASA |

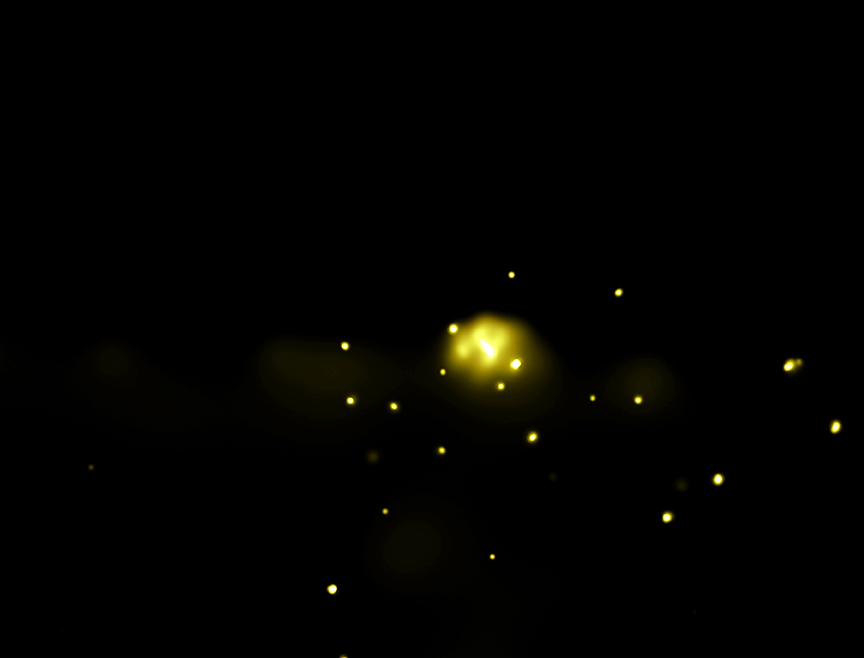

| and X-rays |  Credit: Fred Baganoff (MIT), Mark Morris (UCLA), et al., CXC, NASA |

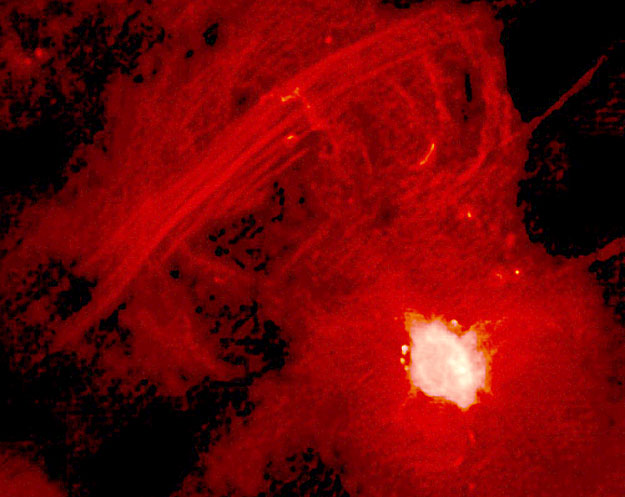

| Close to centre a lot of rapidly moving (300 km/s) hot (i.e. ionised) gas(Gravitational field at centre of galaxy should be very small, so would expect velocities to be small.) and hot stars. Could be very dense cluster of stars..........but note M31 (Andromeda), M100 and many others show a star-like central nucleus |

|

and very rapidly moving stars

|

Credit: A. Eckart (U. Koeln) & R. Genzel (MPE-Garching), SHARP I, NTT, La Silla Obs., ESO |

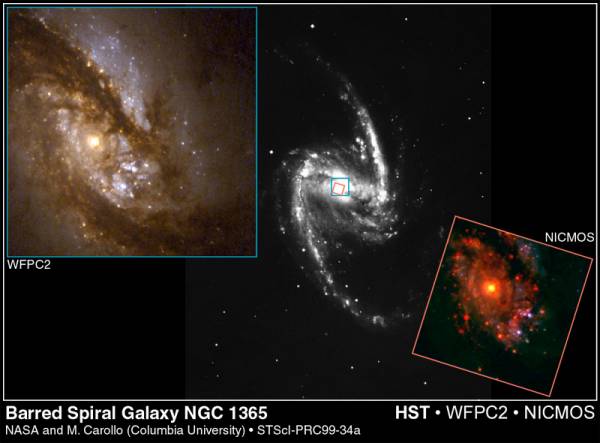

| Whole picture is consistent with a very large black hole at centre, but not nearly as active as we see in other galaxies: e.g. this shows gas at the centre of NGC 1365 |

Credit: Ground-based image: Allan Sandage (Carnegie Observatories), John Bedke (CSC, STScI) WFPC2 image:John Trauger (JPL), NASA NICMOS image: C. Marcella Carollo (JHU, Columbia U.), NASA, ESA |

| e.g giant elliptical galaxy NGC 1275, at the centre of the Perseus cluster, surrounded by a well-known giant nebulosity of emission-line filaments ~ 108 yr old. Mag fields in filaments stop keep them hot & stop star formation. Suspect that there are black holes (1 million to 100 million Mo at the centre of ALL galaxies: these are very different from BH left over from supernovae. |  |

A final consequence:

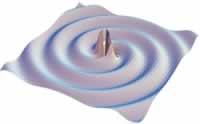

|

|

| Hence (well, more or less hence!) it requires a large amount of mass to produce a grav. wave, and a large amount to see one: e.g need to detect motions of << atomic radius in a one ton sapphire crystal. |  |

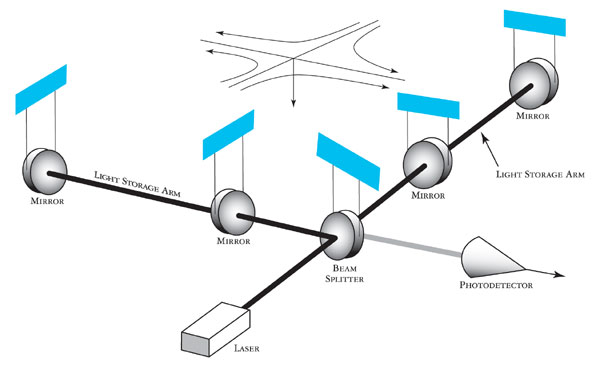

| LIGO (Laser interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory) detectes GW's by interfering 2 beams of laser light after sending them along 4 km arms |  |

| LIGO turned on in 2004: will see coalescing binary systems |  |

This consists of two neutron stars, in orbit 10 km in radius, with period of hours. Change in frequency allows orbit to be calculated exactly, and can measure..

Rate of precession = 4.22662 0/yr (i.e. 30,000x that of Mercury)

and that pulsar is losing energy, by gravitational radiation (mass~1.4 M0, and accns are large)

| Decrease of the orbital period P (about 7h 45 min) of the binary pulsar PSR B1913+16, measured by the successive shifts T(t) of the crossing times at periastron; the continuous curve corresponds to $$ \color{red}{ T(t) = \frac{{t^2 }}{{2P}}\frac{{dP}}{{dt}}} $$ given by the general relativity (reaction to the gravitational waves emission) |  Reference: Taylor J.H. 1993, Testing relativistic gravity with binary and millisecond pulsars, in General Relativity and Gravitation 1992, eds. R.J. Gleiser, C.N. Kozameh, O.M. Moreschi. Institute of Physics Publishing (Bristol). |

Hence 1993 Nobel Prize

Very exhaustive review by Piran, Rev Mod Phys 76, 1143 (Oct. 2004)

Found originally by Vela satellite (designed to look for γ's from nuclear explosions). |

|

| Can identify direction source by using timing with various satellites

Bursts last 1/10 - 100s, no particular pattern |

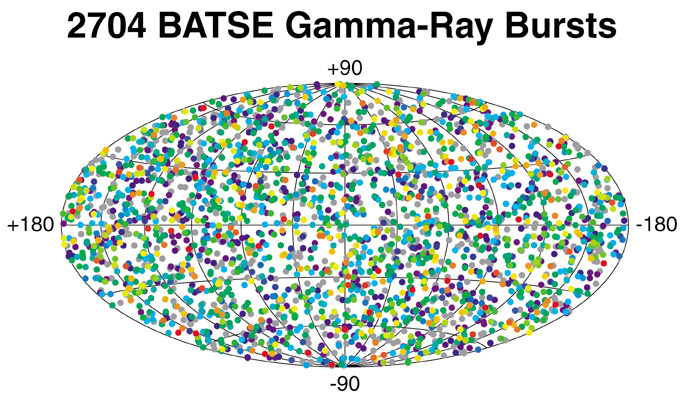

| No connection with ecliptic (unlikely anyway) or with Milky Way. Implies they are not local objects |  |

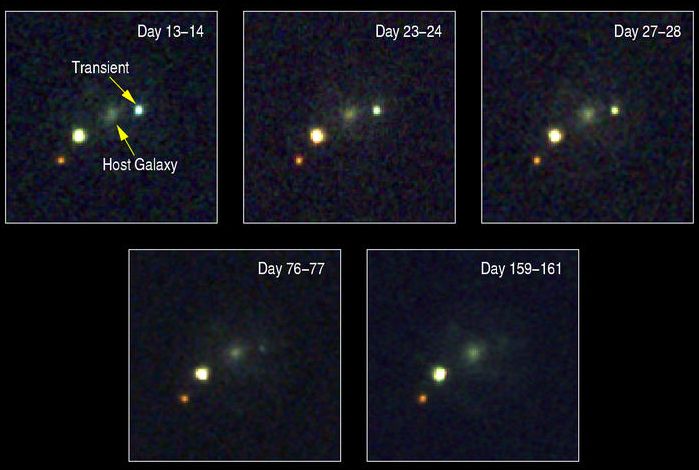

| Optical transients very hard to see |  |

| Gamma-Ray Burst, Supernova Bump : note host galaxy + normal stars |  Image Credit: S. Kulkarni, J. Bloom, P. Price, Caltech - NRAO GRB Collaboration |

| 8 detectors on Compton Observatory: 10keV - 1 MeV |  |

|

|

Two classes: short and long. T90 is time in which 90% of energy is emitted.

|

|